Certain Days art by Jeremy Hammond

Living to Elder by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

Poems by Jennifer Gann

Lack of care leads to deaths in Canadian prisons by RECON

Social health and incarceration by Zoë Christmas

Medical transition and care for trans prisoners by Marius Mason

Health/Care by Kojo Bomani Sababu

What the Government Shutdown Really Means for Federal Prisoners by Daniel McGowan

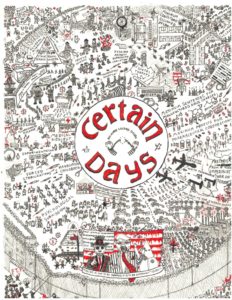

Certain Days art

Check out this amazing art by political prisoner Jeremy Hammond. Though submitted for inclusion in our 2019 calendar, it could not be included due to content. What is and is not allowed into prisons is often vague and spiteful, including art. Though we can’t share this beautiful art with those incarcerated, let’s be sure to share it far and wide on the outside. And be sure to write to Jeremy to show solidarity!

https://freejeremy.net/

https://www.facebook.com/

Jeremy Hammond #18729-424

FCI Milan

Post Office Box 1000

Milan, MI 48160

Living to Elder

By Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

An excerpt from Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice

Since I turned 40, some younger disabled QTBIPOC have started calling me “elder.” While i’m honored, it also makes me feel a little desperate. I know that part of why they’re calling me elder is because I’m the oldest disabled QTBIPOC person they know.

That’s because many sick, disabled, Mad, and neurodivergent older people don’t live to get really old. Sometimes that’s because of progressive disability, but it’s also usually because of systemic oppression. Most of my sick and disabled QTBIPOC elders are in trailer parks or living in a motel or moved back in with their shitty family because they didn’t have a better option.

Other elders I know have more choices but have withdrawn from the world as they’ve gotten older, because lack of access doesn’t get easier as you age. In our 20s and 30s, we might have forced ourselves to be visible to abled people, by organizing and writing and pushing ourselves to be present in abled spaces. But when we hit 40, I see a lot of us being like, fuck it, we’re tired and we can’t push ourselves in the same way anymore. Often our hearts are broken, or very, very tired, from 20 years of struggle. Our friends are dead, our neighborhood has gentrified, and everyone in the queer club is 22 and has no idea of who that old lady/ fag/ butch is. Our bodyminds never fit that well into capitalism, and as we age we fit into it even less.

Young abled people are always like, where are our queer elders? But it’s pretty clear to me where we often are – someplace affordable where we can go to bed early – and what we gain in that move, and also what we lose. My neurodivergent brain and slow body really want some kind of accessible QTBIPOC rural community, but I also get really scared that if I’m not constantly out there as a performer, how fast I’ll be forgotten.

We need to ask ourselves, what are the conditions that will allow disabled QTBIPOC elderhood to flourish? For me, some of those conditions are creating accessible community spaces. When I first moved to Oakland, I was struck by how some of the most popular dance nights for queer women of color happened in the afternoon. They were Black and Latinx queer spaces that went from 2-8 PM, they had free (or $5) barbeque and lots of places to sit down. Those spaces had accessibility, even if no one used the word, that made it possible for me to go dancing. And while I was there, I saw women in their 50s and 60 – dancing and hanging out and being able to be part of a queer women of color social world there. When we really value ourselves queer and trans disabled Black and brown people, the ways our spaces look are going to change- but shit like this proves we already’ve been doing it! We know how to refuse to forget about each other.

Poems

by Jennifer Gann

Earthquakes

Earthquakes of uncontrollable anger,

blood-boiling rage,

turning my face various shades

of red and pink.

Huffing and puffing,

and crying hot tears

which roll down my cheeks.

It has happened over the years,

earthquakes of stupendous joy,

of wondrous changes,

transformation of the self,

of my identity.

Love lost and found

across the landscapes

of concrete and bars,

like cool, sweet, juicy grapes.

Earthquakes in Pakistan,

geopolitical spectrums

from Washington D.C. to Japan

are erupting and shaking.

The world is on the brink

of war and mass destruction.

Too much hatred and violence,

we need more positive production.

Earthquakes of consciousness,

spiritual and political.

As I read and think

and pray to unknown deities

I don’t know what’s next,

but I hope it’s something good.

We should all pause and think

of what it be and what it should!

Do you feel any earthquakes?

The Day I Was Born

On the day i was born

a proud mother cried tears of joy.

Where was my father?

i don’t know if he wanted a boy…

or a girl, maybe?

i cannot even guess.

i would like to ask him,

but he left.

On the day i was born,

i was held by my mother.

She loved me so much,

unlike any other.

i was alive and well,

a brand new life,

crying and kicking,

and breathing in life.

On the day i was born,

it was October 6th, 1969,

after the Summer of Love

and the future was mine.

Happy days, revolutionary days,

and days of love and rage.

Happy days, sad days,

and the day of a New Age.

Happy Birthday!

An Amazon Prayer

I’m lucky to be alive,

tho’ stuck in the Abyss

in this Hell on Earth

called prison.

i’ve learned to thrive,

and faced my fears of Death.

i’m like a rainbow,

an light seen thru a prism.

At first it was hard

and i tended to make things worse.

Resisting injustice,

i was beaten and tortured.

i thought i was cursed.

Twenty-five years and counting,

three strikes and i’m out!

no matter how i’ve changed

or what comes about,

they won’t let me out!

i’ve been stressed and depressed,

traumatized and oppressed,

suicidal more than once,

and my femme gender repressed.

When i came out as trans,

i walked the yard with pride.

i found love and hope again,

and determined never to hide

my SELF – an Amazon!

At times i’m lonely and sad,

thinking of things in Life that i’ve missed,

but Life itself is beautiful,

and i know it’s better than this!

Lack of care leads to deaths in Canadian prisons

By RECON

During October 2017, there were 3 deaths at the Federal Training Centre, a federal prison, in Laval, Quebec. At least two of these deaths would have been preventable with access to proper medical treatment. This article, which is collectively written by people both inside and outside of prison, serves two purposes. The first is to remember these individuals. The second is to contextualize their deaths within the broader issue of inadequate access to care within prisons.

André, an older man who had been diagnosed with cancer and was living with an ostomy bag due to his condition. André was just weeks from release from the prison, but died inside from his cancer. André’s case is not unique – it represents the classic indifference towards suffering that is created by policies within the prison system.

Abdul Ulla, was a 27 year old prisoner suffering from from renal failure and life threatening diabetes. His advanced state of malnutrition was so severe that he represented a skeleton; weighing approximately 90 pounds. His medical issues placed him at the infirmary three times a day for dialysis. After a disagreement with medical staff around him accessing timely care, CSC staff – instead of acknowledging his medical needs as pressing – took the disagreement personally. He was placed in solitary confinement. He was treated as a prisoner before he was treated as a person. Abdul was later found in a diabetic coma. He died after failed resuscitation attempts by prison staff. The severity of his medical issues should have prevented him from ever being placed in solitary confinement. Abdul should have been receiving adequate care. Instead, he too died alone, before the age of 30.

Tasha, a transgender woman serving a life sentence, had complained of severe respiratory pain for weeks. She was continuously refused access to adequate care. Had she been outside of the prison, any number of resources would have been available to her, including the ability to seek a second medical opinion and gain access to the correct course of treatment. Her health concerns were not taken seriously until it was too late. Tasha died alone in her cell after more than 30 years in prison. After such an extended sentence, she had little connection to an outside community. All prisoners are required to keep $80.00 in their savings accounts to pay for death related costs, especially in the instance that there should be no family or outside support to claim the body. Tasha was no different. She was buried in a body bag, on prison property. Her grave includes no indication or marker, besides a number. The brutal anonymity of Tasha’s death is undeniable but it is not an isolated incident.

Deaths in prison are not only in the hands of correctional staff. The prison industrial complex implicates us all – those in prison, and those on the outside. No matter how distant the prisoners and the prison system may feel, our existence in a society relying on prisons holds us all accountable. All deaths in prison should be understood as preventable because prisons are not the only option.

Social health and incarceration

By Zoë Christmas

In 1972, when Huey Newton formally added the demand for free health care to the Black Panther Party’s Ten-Point Program, the mandate mostly reflected a need for medical facilities and coverage. Yet, the Black Panthers were committed to a holistic approach to health care, seeing it as both a bodily and environmental phenomenon. As such, their programs ranged from ambulance services in black communities, to the Free Busing to Prison Program, which connected incarcerated blacks to their loved ones and communities.

In the 47 years since Newton’s declaration, there has been little improvement in the greater system. Indeed, health care standards are compromised for incarcerated individuals. Social well-being is a particularly underfunded and underserved component of prison life, which leaves some prisoners without access to basic liberties, such as education, books and affordable phone calls. Programs are limited for formerly incarcerated folks as well – under Trump, the American Bureau of Prisons has cut funding to halfway houses for cognitive behavioral therapy and various social services, including job and housing support.

Social health in prison could include therapeutic, community and creative programs that not only help rehabilitate people, but could eventually, if widely applied, dismantle what incarceration means and how it is manifested. A number of restorative justice pilot programs that aim to transform prison culture have been proposed over the past few decades. A program called Resolve to Stop the Violence Project (RSVP) was established in 1997 in California. RSVP is rooted in male role-rebuilding and accountability. The project sensitizes violent offenders to empathy, gives them a chance to listen and speak to survivors of violence, offers addiction recovery, and embraces creative expression and positive contributions to the community.

Another pilot project was launched in 2017 at Cheshire Correctional Institution in Connecticut. Truthfulness, Respectfulness, Understanding, and Elevating (TRUE) lets older prisoners become mentors for young offenders, letting them to reshape their environment, help develop emotional growth and make peace with their vulnerabilities. The program also allows more relaxed and intimate visits from friends and family. Inspired by prisons in Germany, where folks can cook their own food and wear the own clothes, TRUE strives for empathy, therapy and rehabilitation as opposed to punishment.

While pilot projects like RSVP and TRUE embrace restorative justice, prevent recidivism, and foster an environment that curbs violence and volatility behind bars, they do not address the fundamental issues of these institutions, namely the racist, classist and ableist forces of the criminal justice system. The inherent role of capitalism in incarceration, moreover, suppresses prisoner health, sustains for-profit abuse, and perpetuates a culture of brutality and exploitation that targets marginalized communities. Prisons and jails remain establishments that feed off of oppression, despite experiments with rehabilitative and restorative social programs. A crucial point of the Black Panther’s platform is the abolition of incarceration: According to their 1972 mandate, the party calls for, “the ultimate elimination of all wretched, inhuman penal institutions, because the masses of men and women imprisoned … are the victims of oppressive conditions which are the real cause of their imprisonment.” Indeed, health cannot be realized until freedom is granted to all.

Zoë Christmas is a law student at McGill University in Montréal. She helps coordinate Open Door Books, a prison-books collective based in QPIRG Concordia, and is passionate about prison justice and abolitionism.

Medical transition and care for trans prisoners

By Marius Mason

It has been a slow slog through many bureaucratic cesspools, but there is a small community of trans men and women at Carswell, FMC who are pursuing medical transition as part of their care as trans prisoners. We have encountered many invisible (to us) barriers to receiving care, and that has been damaging to a few of us who have been waiting many years to get any kind of support at all.

It is so common, this delay in care, in the federal prison system, that it is important to note that trans care is an exaggeration even of those common delays. Some of the trans inmates that I have spoken to have waited more than a decade, as they had been advocating before the landmark policy change case in 2013. But even after that change in policy, a real change in actual care has been slow.

In my own case, I went through more than 2 years of every test imaginable before I was cleared for the medical care I had requested and needed to treat my gender dysphoria. My hormone levels have been aggressively tested (weekly at first), as a way to deny administering a level of testosterone that would effectively change my appearance to be more masculine. I am at what would be deemed a “maintenance” level, and cannot get information as to why this is, other than the verbal assurance that “my levels are too high”. How high are they? I don’t know, because I am not allowed to have a copy of my medical records or to know what my levels are, or the results of any of the tests that have been done on me. This is considered confidential because of security concerns, even though I am openly trans and am listed as such in the BOP database.

It has also been frustrating to not be able to track the status of my request for re-assignment. The task force/committee that is assigned to review requests has not met since this new administration took office, though they are legally bound to meet twice a year. I have been told by both psychology staff and by the assistant warden over medical issues that my request was forwarded on to the committee and that no further information is available. My request was forwarded in October 2017. I have been on testosterone since September 14th of 2016, and have clearly completed the year required by policy before requesting surgery – as have other trans men and women now on this compound.

If policy is changing, there has been no official notification… only this delay which results, in fact, with the denial of care. Trans people have made some significant progress in terms of visibility and public understanding of our issues, but like so many other prisoners – we have far fewer rights to medical care than our free comrades. I hope that our community on the outside will help us to access the medical care we need. Thank you for whatever support you can offer.

Marie (Marius) Mason #04672-061

FMC Carswell

P.O. Box 27137

Fort Worth, TX 76127

Please address letters to “Marie (Marius) Mason.” Contrary to previous reports, Carswell is not accepting mail addressed to “Marius.”

Health/Care

Essential health/care has been reduced to a single factor, income!! If treating you generates revenue for the health/care industry the care necessary to provide excellent treatment will prevail. However, if profit cannot be maximized the disease or medical issue is overlooked.

Currently I suffer from a cardiac and lung problem. The committee that oversees healthcare for the incarcerated in federal institutions keeps denying a transfer to a hospital or an institution adequate to provide safe healthcare.

This problem of inadequate healthcare and services not only resides on the outside but also within the prisons and institutions of America. Disease prevention programs (e.g. clean environments) separating those that are ill with transferable symptoms are kept amongst the general population. Many who are released return to society with diseases transmitted in prison.

The movement’s call should be that healthcare should and must be affordable to everyone, whether inside or outside and it should be universally applied to anyone who needs such.

Kojo Bomani Sababu (Grailing Brown)

#39384-066

USP Canaan

P.O. Box 300

Waymart, PA 18472